Difference between revisions of "Guide to Character Annotation"

(→2a. Examples of structural qualities between two entities) |

(→2b. Examples of positional qualities between two entities) |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

* unfused from | * unfused from | ||

| − | ====2b. | + | ====2b. Positional qualities between two entities==== |

The following are position qualities used to describe the position or orientation of an entity relative to another entity. Note that some positional qualities apply to single entities only (see 1b above). | The following are position qualities used to describe the position or orientation of an entity relative to another entity. Note that some positional qualities apply to single entities only (see 1b above). | ||

Revision as of 22:30, 12 May 2015

This page describes the best practices and guidelines for using EQ syntax to consistently and accurately represent phenotypes from the systematic literature. The guidelines are an evolving set of standards created to improve annotation consistency for the use cases and goals of the Phenoscape project. We provide examples of character types commonly encountered in the systematics literature, and provide discussion of special cases and issues in their annotation.

The Entity-Quality (EQ) formalism combines ‘Entity’ terms from an anatomical ontology, in our case Uberon, with ‘Quality’ descriptors from the Phenotype and Trait Ontology (PATO). Spatial and positional terms from the Biological Spatial Ontology (BSPO) are also used to represent phenotypes.

Contents

- 1 PATO terms used to annotate systematic characters

- 2 Annotation Specificity

- 3 Character Annotation Examples

- 3.1 1. Qualities of single physical entities

- 3.2 2. Qualities of related physical entities

- 3.3 3. Size

- 3.4 4. Biological process annotations

- 3.5 5. Sexually dimorphic phenotypes

- 3.6 6. Quality-modified entities and 'present'/'absent' annotations

- 3.7 7. Bilaterally paired structures

- 3.8 8. Complementary phenotypes ("negation")

- 3.9 9. Use of skeletal terms (bone, cartilage, skeletal element)

- 4 Interpreting Authors' Text

- 5 Creating or refining terms by post-composition

- 6 === Relations used for post-compositions=

- 7 Evidence Codes

PATO terms used to annotate systematic characters

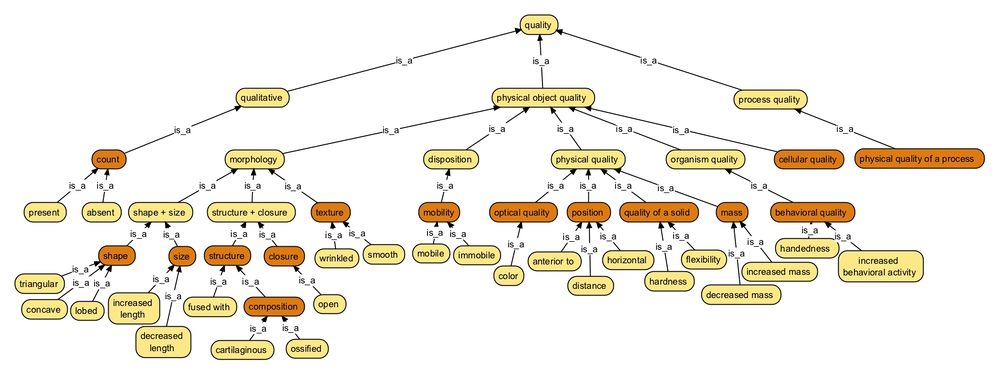

Below is a simplified graph showing a subset of quality terms from the Phenotype and Trait Ontology (PATO) used to curate systematic characters. Terms in orange represent attribute-level qualities.

| PATO attribute-level term | Synonyms | Examples of child terms |

|---|---|---|

| shape | triangular, lobed, concave, protruding into | |

| position | placement, location | horizontal, anterior to |

| size | thin, large, decreased height | |

| structure | porous, fused with | |

| composition | composed of, content | ligamentous, cartilaginous |

| texture | smooth, wrinkled | |

| optical quality | color, brightness | |

| mass | increased mass | |

| quality of a solid | flexible, hard | |

| mobility | mobile, immobile | |

| closure | open, closed | |

| behavioral quality | ||

| count | number, amount | present, absent |

Annotation Specificity

Annotations are made using the most specific term or post-composition possible for Entity and Quality. This may not be possible for some characters involving very complex phenotypes, particularly those describing shape variation. In these cases, annotations are made to 'attribute' level PATO terms (e.g., PATO: shape).

Character Annotation Examples

The following are examples of character types commonly encountered in the systematic literature and how we annotate them using the Entity-Quality (EQ) model in Phenex. A character state can often require multiple EQs to capture all of the anatomical details described by an author. For example, a state may describe “premaxillary teeth round and multicuspidate." This is represented with the following two phenotypes:

E: premaxillary tooth, Q: round E: premaxillary tooth, Q: multicuspidate

Abbreviations: E = anatomical entity from Uberon; Q = Quality term from PATO, RE = related anatomical entity, C = count (numerical value).

1. Qualities of single physical entities

Many qualities in PATO apply only to single entities (e.g., 'shape,', 'count', 'open') without reference to a second, related entity (RE). Examples of qualities of single physical entities are given below. Other qualities are "relational" and must be used with a second, related entity (e.g., 'fused with'; more examples in #2). Finally, some qualities can be used either with or without a second entity (e.g., 'increased size').

1a. Shape

All shape terms apply only to single entities. Example: “sigmoid-shaped supraorbital bone” is annotated as:

E: supraorbital, Q: sigmoid

1b. Position

Some position terms apply only to single entities (see 2b. below for position terms applicable to two entities).

E: projection part_of frontal, Q: vertical

1c. Count

'Count' is used to record the number value(s) of an entity. Values for counts are recorded in the “Count" field (Note: due to a Phenex bug, the Count field only accepts integer values; ranges ("3-5") or symbols ("≥") must be recorded in the "Comment” field). Some examples:

E: vertebra, Q: count, Count: 33

E: vertebra, Q: count, Comment: 34-38

E: vertebra, Q: count, Comment: >38

E: vertebra, Q: count, Comment: ≥48

1d. Presence/Absence

PATO: present and absent are used to annotate variation in the presence of entities, e.g.:

E: pectoral fin, Q: present

(Technical note: The use of present and absent in curation is a curatorial shortcut to the more logically sound syntax discussed on the PATO wiki. Presence annotations in Phenoscape are translated into this logically sound form prior to their addition in the Phenoscape KB.)

Inferred presence from annotation to other attributes. It is not necessary to annotate the presence of an entity if the character describes some other attribute regarding its features . For example, "frontal bone present and round" requires only one annotation: E: frontal bone Q: round because the presence of frontal bone is inferred by this annotation.

Some phenotypes describe a state that exists between two entities. In these cases, relational qualities are used to relate the two entities. Examples of relational qualities include 'differetiated from', 'overlapped by', and 'fused with':

E: parietal bone, Q: fused with, RE: supraoccipital bone

Note: some qualities in PATO can be used with either single entities OR with two entities (for example, PATO: increased size). A partial list of PATO terms that require related entities are listed below in 2a and 2b.

2a. Structural qualities between two entities

- separated from

- attached to

- in contact with

- fused with

- unfused from

2b. Positional qualities between two entities

The following are position qualities used to describe the position or orientation of an entity relative to another entity. Note that some positional qualities apply to single entities only (see 1b above).

- anterior to

- posterior to

- diagonal to

- extends to

- basal to

2c. Fusion and contact qualities

Fusion of skeletal elements can be described using the relational qualities ‘fused with’ and ‘unfused from’. The latter term (‘unfused from’) can apply whether or not two elements are in contact with each other. If an author explicitly describes the contact between two elements, the qualities ‘in contact with’ and ‘separated from’ should be used. Note that all of the mentioned qualities require a second related entity.

3. Size

There are various ways an author may describe or compare the size of a structure across taxa. These are summarized below:

3a. Relative size comparisons compare the size of two structures. For example, "frontal length greater than parietal length" is represented as:

E: frontal bone, Q: increased length, E2: parietal

3b. Size comparison across taxa. For example, a state describing "frontal large” is annotated as below. Note that the EQ does not require annotation to terms from a taxonomy ontology because the matrix saved in the Phenex file has a mapping from states to taxa.

E: frontal bone, Q: increased size

3c. Multiple dimensions of size may be described for a single structure. For example, an author may describe the frontal bone as having a "greater length relative to width". This requires post-composing the Quality with PATO: "length" and PATO:"width":

E: frontal bone, Q: length^increased_in_magnitude_relative_to(width^inheres_in(frontal bone)

We are currently annotating to this detailed level. A less detailed ("coarse") way to represent the above phenotype is:

E: frontal bone, Q: increased length, RE: frontal bone

3d. Series of relative sizes describes a range of sizes in more than two states. For example: "maxilla: (0) long, (1) medium, or (2) short". Choose the relevant size quality being compared, and place a number in the Count column indicating the proper sort order (e.g., 1 < 2 < 3... for short < medium < long ...). For "short":

E: maxilla, Q: length, Count: 1

3e. Size variation from a "normal" or "typical" state: For example: "femur size: (0) small, (1) typical size. State 1 does not imply imply that the femur is large (thus, PATO:‘increased size’ should not be used) but state 1 is distinguished from state 0 by NOT being small in size:

E: femur, Q: decreased size (state 0) E: femur, Q: size not decreased size (state 1)

3f. Similarity in 'size' and 'shape' terms. Many aspects of size variation also relate to shape (and vice versa). For example, the terms PATO:"increased width" (with related synonym: "broad") and PATO:"broad" are separate terms that have different parent terms in the ontology, despite describing very similar phenotypes. "Increased width" has ‘size’ as its parent whereas "broad" has "shape" as its parent. By convention, we use "increased width" to indicated variation in the size dimension.

Technical note: Curatorial shortcuts are used in Phenex to represent size, in place of requiring curators to create the complex but semantically correct post-compositions otherwise required. In PATO, the terms "increased size" and "decreased size" (along with their children) are precomposed relative to "normal" (e.g., increased size has an increased_in relationship to "normal"). Because the "normal" phenotype does not apply to systematic characters, these annotations will be converted in the KB data loader to the correct form using the appropriate relations (increased_in_magnitude_relative_to, decreased_in_magnitude_relative_to, similar_in_magnitude_relative_to).

4. Biological process annotations

Some phenotypes describe variation related to biological processes (e.g., tooth development) and in such cases, terms are taken from the 'biological process' (GO:0008150) branch of the Gene Ontology. Biological process terms can only be used with ‘process quality’ (PATO:0001236) terms in PATO.

5. Sexually dimorphic phenotypes

Phenotypes specific to males or females are defined using the Uberon terms ‘male organism’ and ‘female organism’. For example, “Male cloacal folds, absent” is represented as

E: cloacal fold^part_of(male organism), Q: absent

6. Quality-modified entities and 'present'/'absent' annotations

Sometimes it is necessary to use a PATO term to modify an entity in post-composition. For example, an author may describe the "number of round teeth":

E: 'tooth' bearer_of some 'round'; Q: 'count'

In other cases, we will want to avoid creating a post-composition. For example, consider the character: "branched dorsal fin ray, present or absent". In this case, we interpret the character as describing the quality of the fin rays being 'branched' or 'unbranched', rather than present or absent:

E: dorsal fin ray; Q: branched E: dorsal fin ray: Q: unbranched

Implications on reasoning. It may appear that there are two similar ways to annotate such characters: for example, consider the presence/absence of white hair:

E: 'hair' bearer_of some 'white'; Q: 'present'

This is different from:

E: 'hair' Q: 'white'

The first annotation describes the presence of some white hair, whereas the second annotation describes *all* hair being white . Generally, we want to use quality modified entities when annotating these types of complex EQs.

7. Bilaterally paired structures

Terms for the contralateral halves of bilaterally paired structures are created using the in_right_side_of and in_left_side_of relations in a post-composition, where the perspective is from the standpoint of the organism. For example:

E: frontal^in_right_side_of(whole organism), Q: fused with, RE: frontal^in_left_side_of(whole organism)

8. Complementary phenotypes ("negation")

Example: "opercle, not round". Create a postcomposition for the quality, choosing a meaningful genus term and using the "not" relation.

E: opercle, Q: shape^not(round)

See also 3e above for examples of size variation from a "normal" or "typical" state.

9. Use of skeletal terms (bone, cartilage, skeletal element)

Authors sometimes refer to endochondral structures without specifying whether the structure is “bone” or “cartilage.” For example, the convention for a term like “epibranchial 2” or “basibranchial” is that it is composed of bone and when composed of cartilage an author will say “epibranchial 2 cartilage” or “basibranchial cartilage”. However, this is not universally followed and a curator must read the character description and examine associated text and figures to ascertain this. If after reviewing the publication it is still not clear, then the curator can use the “element” term for the structure. In general, the “element” terms should be used sparingly, and only when an author does not indicate whether a structure (e.g. “epibranchial”) is composed of cartilage or bone.

Note: in paleontological studies, authors may describe an element as "unossified", which is interpreted as the absence of the bone element (see example 7). However, if the matrix of a paleo paper contains extant taxa, ossified for extant taxa means that the element is cartilaginous.

The following are a series of examples demonstrating the use of bone, cartilage, and element terms.

Example 1

Epibranchial 1 bone: (0) present

E: epibranchial 1 bone, Q: present

Epibranchial 1 bone: (1) absent

E: epibranchial 1 bone, Q: absent

Example 2

- Epibranchial 1: (0) present and ossified.

E: epibranchial 1 bone, Q: present

(Note that the annotation "epibranchial 1 cartilage, absent" is not needed)

- Epibranchial 1: (1) present and cartilaginous

E: epibranchial 1 cartilage, Q: present

(Note that the annotation "epibranchial 1 bone, absent" is not needed)

- Epibranchial 1: (2) absent

E: epibranchial 1 cartilage, Q: absent E: epibranchial 1 bone, Q: absent

The curator should use both the cartilage and bone terms to annotate state 2 because the author clearly differentiates between the two.

Example 3

Epibranchial 1 (0) present, (0) absent. After careful reading of associated text in the publication, the curator cannot conclude that the author refers to bone or cartilage, and therefore uses "element" term:

E: epibranchial 1 element, Q: present E: epibranchial 1 element, Q: absent

Example 4

Epibranchial 1: (0) triangular. After careful reading of associated text in the publication, the curator cannot conclude that the author refers to bone or cartilage, and therefore uses "element" term:

E: epibranchial 1 element, Q: shape

Example 5

Epibranchial number: (0) 3; (1) 4. After careful reading of associated text in the publication, the curator cannot conclude that the author refers to bone or cartilage, and therefore uses "element" term:

E: epibranchial element, Q: Count 3 (State 0) E: epibranchial element, Q: Count 3 (State 1)

Example 6 -- Convention used in paleontology

The convention in paleo studies is to use "unossified" when no trace of the skeletal element is present. It does not imply that cartilage is present or absent. For example:

Pubis: (0) unossified, (1) ossified

E: pubis (is_a bone), Q: absent E: pubis (is_a bone), Q: present

Example 7 -- 'Presence of dermal elements

Cleithrum: (0) unossified; (1) ossified

E: cleithrum, Q: absent (State 0) E: cleithrum, Q: present (State 1)

Interpreting Authors' Text

Authors may sometimes describe characters with words that have exact matches to ontology terms, but these exact term matches may not chosen by a curator for various reasons. For example, a character may describe: “Clavicle shape of ventromedial plate: narrow, deep, intermediate”. “Deep” has an exact match in PATO but given the context of the other states and the curator’s knowledge of this particular anatomy, the curator decided that “deep” refers to an increase in width and therefore chose PATO: increased width to annotate this state.

Another example relates to the PATO terms for continuous, discontinuous and offset quality. These are children of process quality in PATO and therefore should not be used in the context of anatomy. However, authors sometimes use these terms to describe qualities of margins (continuous, discontinuous) and position (offset). Other PATO terms are more appropriate for these annotations (e.g., straight, offset).

Creating or refining terms by post-composition

Often times the need arises to create a new term at the time of annotation ("post-composition"), rather than requesting that the new term is formally added to the ontology. Such cases typically arise when annotating the presence of processes on bones. In some cases a more granular term is required than is already present in the ontology, whether it is the anatomical entity or the quality. For example, to prevent ontology "bloat", regions, margins, and projections of a bone are not in the anatomy ontology, but the bone itself is, and the concepts of margin, relative location of the margin (anterior, posterior, ventral, dorsal, etc), or bony projection are too, or are in other ontologies (spatial aspect, for example). Similarly, the directionality of a phenotype (such as a rotation, or curvature) isn't necessarily present in PATO, but the component terms necessary to express it are. The act of combining terms on-the-fly into cross-product terms is called post-composition, as opposed to pre-composed terms that are already in the ontology.

Post-composed terms can be created in Phenex following the genus-differentia principle of defining terms, where one term serves as the genus, which is then differentiated using a relationship and a differentia term. Unlike pre-composed terms, post-composed terms do not have an ID, and hence are "anonymous." Therefore if the same post-composition is used multiple times, it has the same semantics, but not the same identity. For example, if one wants to assign multiple annotations to the same process of the lateral ethmoid in the same specimen, using post-composed terms does not allow the identity of the anatomical structure between the annotations to be inferred.

The order in which the terms are composed is important if the composition relationship is not symmetric (a relationship is symmetric iff A rel B <=> B rel A). Most relationships are not symmetric. As a general rule, choose the more general part as the genus, and then use the relationship and differentia to narrow down. For example, for "process of the lateral ethmoid" use "process" as the genus, and use the relationship and differentia to narrow down which process of the many that are possible you mean, such as using part_of for the relationship and "lateral ethmoid" as the differentia (formally, the "process that is part_of the lateral ethmoid").

Note that semantically, the post-composed term is equivalent to a pre-composed term, provided the pre-composed term has both the inheritance relationship and the cross-product relationship properly recorded. For example, "process of lateral ethmoid" is-a "process", and "process of lateral ethmoid" part-of "lateral ethmoid".

Creating post-composition in Phenex

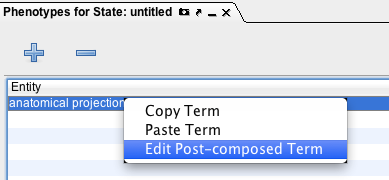

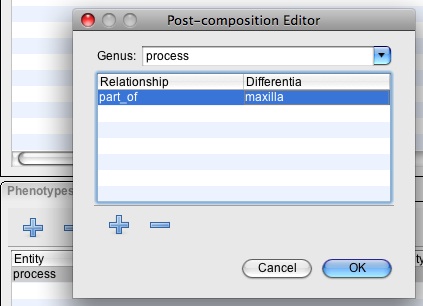

To post-compose a term (for example, "maxillary process") using Phenex, first type in the genus term 'process' in the Entity field within the "Phenotypes" panel. Then open the Post-composition Editor box by right-clicking on the Entity cell (make sure that the entity cell is blue in color) :

Now click on “Edit Post-composed Term.” The Editor box should now appear (see below), with “process” in the Genus field. The Genus is the feature of specific interest (varying feature in systematics). Click the “+” button to add a row in the table, type “part_of” in the relationship field, and type “maxilla” in the differentia field. Click OK.

process^part_of(maxilla)

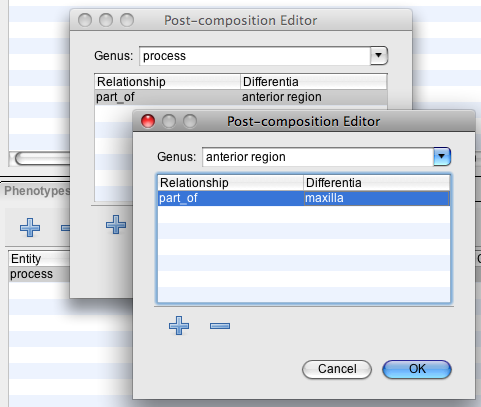

Refining post-compositions using terms from the Spatial Ontology (BSPO)

The Spatial Ontology (BSPO) is used to post-compose terms related to the margins, surfaces, or regions of skeletal elements. For example, the entity “anterior process of the maxilla" is post-composed as follows:

anatomical projection^part_of(anterior region^part_of(maxilla))

Use of terms for regions vs. sides in BSPO: Regions are defined as not having well-defined boundaries, unlike sides. For post-compositions, we usually annotate using region terms because the placement of processes on skeletal elements aren't described with very much detail. For example, if an author describes the dorsal process of some bone, then we post-compose "process part of dorsal region part of bone". This also applies to an author describing the shape of a portion of a skeletal element.

To create post-compositions using BSPO in Phenex, right click the Entity field to bring up the post-composition editor box. Type “process” and right-click the field to open the Post-Composition Editor box. Within this box, Click the + button to add relationship = "part_of" and differentia = "anterior region". Right click on the differentia field to open another Post-Composition Editor box to add second post-composed term for "anterior margin of maxilla" (see below). Click the OK button after you have filled out the genus and differentia for this nested composition.

Within Phenex, the post-composed term for process on the anterior margin of the maxilla appears as: process^part_of(anterior region^part_of(maxilla))

As for semantics, identifiability, and rules for post-composing, the same applies as above for entity terms applies to spatial terms. In creating the nested term "anterior region of maxilla", start with the more general term (for example, the "anterior region") as the genus, then refine it using a relationship and a differentia term (for example, anterior region that is part_of the "supraorbital bone").

Multiple differentia terms and nesting in post-composition

Post-compositions can contain multiple differentia terms that are either nested:

anatomical project^part_of(anterior region^part_of(maxilla))

or not nested:

joint^connects(metapterygoid)^connects(hyomandibula)

For nested post-compositions, the order of nested terms is important (e.g., maxilla^part_of(anterior region^part-of(anatomical projection)) is incorrect), as is the nesting itself (e.g., anatomical projection^part_of(anterior region)^part_of(maxilla) is incorrect).

Some post-compositions with multiple differentia do not require nesting (see discussion of joint post-compositions).

Creating "joint" terms on-the-fly

Joints are defined in Uberon according to the skeletal elements that participate in the joint. The connects relation is used to relate skeletal elements to skeletal joints. We post-compose joint terms that are not likely to be used repeatedly for annotation. To post-compose a joint, for example the "metapterygoid-hyomandibular joint", use the post-composition editor box by right-clicking on the Entity field and compose the following term. Note that this expression is not nested.

skeletal joint^connects(metapterygoid)^connects (hyomandibula)

=== Relations used for post-compositions

=

| Relation |

Category | Design Pattern |

Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| anteriorly connected to | connectedness | E anteriorly_connected_to E |

'head' and (anteriorly_connected_to some 'neck') |

| attaches_to | connectedness | E attaches_to E |

Used primarily to represent attachment of teeth, scales, and ligaments. Examples:

'tooth' and (attaches_to some 'maxilla') 'scale' and (attaches_to some 'caudal fin') NOTE: Teeth and scales are not always related to structures by attaches_to; they can also be part_of an anatomical structure, e.g., 'tooth' part_of (some 'dentition') or 'scale' (part_of some 'scale row') |

| connected_to |

connectedness | E connected_to E |

Used between entities of the same general type. For example, cities, bones, neurons 'sternum' and (connected_to some 'rib') |

| connects |

connectedness |

E connects E |

Used between the entity facilitating the connection and each entity on either side. For example, roads, joints, axons + synapses.This is used to post-compose terms for joints. For example, metapterygoid-hyomandibular joint is post-composed as: 'joint' and (connects some 'metapterygoid') and (connects some 'hyomandibula') |

| distally_connected_to | connectedness | E distally_connected_to E |

'leg' and (distally_connected_to some 'pes') |

| posteriorly connected to | connectedness | E posteriorly_connected_to E |

'neck' and (posteriorly connected to some 'trunk') |

| proximally connected to | connectedness | E proximally_connected_to E |

'forelimb skeleton' and (proximally_connected_to some 'pectoral girdle skeleton') |

| develops_from | development | E develops_from E |

'endochondral bone' and (develops_from some 'cartilage element') |

| has_muscle_insertion | muscle attachment | 'muscle X' has_muscle_insertion E |

'triceps brachii' and (has_muscle_insertion some 'olecranon') |

| has_muscle_origin | muscle attachment | 'muscle X' has_muscle_origin E |

'triceps brachii' and (has_muscle_origin some 'humerus') |

| serves_ as _attachment _site_ for | muscle attachment | E serves_as_attachment_site_for muscle X |

anatomical projection^serves_as_attachment_site_for(triceps brachii)^part_of(coracoid bone) Note: this post-composition is not nested |

| has_part | mereological | E has_part E |

'premaxilla' and (has_part some 'anatomical projection') |

| part_of | mereological | E part_of E |

'anatomical projection' and (part_of some 'premaxilla') |

| bearer_of |

quality | E bearer_of Q |

tooth' and (bearer_of some 'tapered') Note: bearer_of is most likely used as a modifier of an Entity term, not used in Quality field |

| inheres_in | quality | Q inheres_in E |

'length' and (inheres_in some 'coracoid bone') |

| decreased_in_magnitude_relative_to |

size | Q decreased_in_magnitude_relative_to Q |

[1]E: frontal bone, Q: length^decreased_in_magnitude_relative_to(width^inheres_in(frontal bone)) |

| increased_in_magnitude_relative_to |

size |

Q increased_in_magnitude_relative_to Q |

[1]E: frontal bone, Q: length^increased_in_magnitude_relative_to(width^inheres_in(frontal bone)) |

| similar_in_magnitude_relative_to |

size | Q similar_in_magnitude_relative_to Q |

[1]E: frontal bone, Q: length^similar_in_magnitude_relative_to(width^inheres_in(frontal bone)) |

| adjacent_to | spatial | E adjacent_to E |

|

| anterior_to | spatial | E anterior_to E |

'basal fulcrum' and (anterior_to some 'dorsal fin') |

| deep_to | spatial | E deep_to E |

|

| distal_to | spatial | E distal_to E |

'radial' and (distal_to some 'ulnare') |

| dorsal_to | spatial | E dorsal_to E |

'anatomical region' and (dorsal_to some (glenoid fossa and (part_of some 'scapula') |

| encloses | spatial | E encloses E |

|

| extends_from | spatial | E extends_from E |

'anatomical surface' and (extends_from some 'parietal bone') |

| extends_to | spatial | E extends_to E |

'anatomical surface' and (extends_to some 'frontal bone') |

| has_cross_section | spatial | ||

| in_anterior_side_of | spatial | E in_anterior_side_of E |

|

| in_distal_side_of | spatial | E in_distal_side_of E |

|

| in_lateral_side_of | spatial | E in_lateral_side_of E |

|

| in_left_side_of | spatial | E in_left_side_of E |

'frontal bone' and (in_left_side_of some 'body') |

| in_median_plane_of | spatial | E in_median_plane_of E |

|

| in_posterior_side_of | spatial | E in_posterior_side_of E |

|

| in_proximal_side_of | spatial | E in_proximal_side_of E |

|

| in_right_side_of | spatial | E in_right_side_of E |

'frontal bone' and (in_right_side_of some 'body') |

| posterior_to | spatial | E posterior_to E |

|

| proximal_to | spatial | E proximal_to E |

|

| surrounded_by | spatial | E surrounded_by E |

|

| surrounds | spatial | E surrounds E |

'anatomical projection' and (surrounds some 'popliteal area') |

| ventral_to | spatial | E ventral_to E |

|

| vicinity_of | spatial | E vicinity_of E |

|

| not | Q not Q |

Used to represent complementary phenotypes, for example: 'shape' and (not some 'round') |

==

Evidence Codes

**Note: Does not apply to current curation

We record phenotype descriptions as properties of species, and annotations are assigned one of three evidence codes based on the level of evidence given by an author for phenotype observations. These specimen evidence codes are in an Evidence Codes Ontology that was developed by the broader biological community (see http://obofoundry.org/cgi-bin/detail.cgi?id=evidence_code). We have added evidence codes to this ontology, and we use the following in order below from strong to weak evidence.

Inferred from Voucher Specimen (IVS)

Used when an annotation is made on the basis of a phenotype description for a species or higher level group that is given by an author who explicitly references an observation of a voucher specimen(s). Voucher specimens are defined as those specimens with permanent museum catalog numbers. Thus it would be possible for a person to examine this particular specimen and observe the annotated phenotype.

- Note: if there is a matrix in the paper, the IVS evidence code is assigned to all annotations linked to the character list.

Traceable Author Statement (TAS)

The TAS evidence code covers author statements that are attributed to a cited source. Typically this type of information comes from review articles. Material from the introductions and discussion sections of non-review papers may also be suitable if another reference is cited as the source of experimental work or analysis. When annotating with this code the curator should use caution and be aware that authors often cite papers dealing with experiments that were performed in organisms different from the one being discussed in the paper at hand. Thus a problem with the TAS code is that it may turn out from following up the references in the paper that no experiments were performed on the gene in the organism actually being characterized in the primary paper. For this reason we recommend (when time and resources allow) that curators track down the cited paper and annotate directly from the experimental paper using the appropriate experimental evidence code. When this is not possible and it is necessary to annotate from reviews, the TAS code is the appropriate code to use for statements that are associated with a cited reference. Once an annotation has been made to a given term using an experimental evidence code, we recommend removing any annotations made to the same term using the TAS evidence code.

Nontraceable Author Statement (NAS)

The NAS evidence code should be used in all cases where the author makes a statement that a curator wants to capture but for which there are neither results presented nor a specific reference cited in the source used to make the annotation. The source of the information may be peer reviewed papers, textbooks, database records or vouchered specimens.