Guide to Character Annotation

Contents

How to write definitions for ontology terms

Genus-differentia definitions

Term definitions in the teleost anatomy ontology (TAO) take the form of genus-differentia definitions: B is an A that has X. The term B is defined by its membership in higher category A and distinguished from its sibling terms by characteristic X. The following are examples of genus-differentia definitions in the TAO:

Antorbital: Dermal bone that is located on the anterior margin of the infraorbital series, dorsal to the first infraorbital and lateral to the nasal bone.

Dentary: Dermal bone that forms the anterolateral part of the lower jaw.

In example 1, the definition mentions the parent dermal bone of the term antorbital, followed by the characteristics that differentiate antorbital from all other dermal bones.

Post-composed terms (described below) are terms created on-the-fly at the time of annotation, and take the form of genus-differentia definitions.

Character types

The following are examples of character types commonly enountered in the systematic literature and how we annotate them using the EQ model in Phenex. Abbreviations: E, entity; Q, quality, RE, related entity, C, count.

Presence/absence characters

E: pectoral fin, Q: present E: pectoral fin, Q: absent

You might see “presence” appear in the Quality field drop down menu, as it is the parent term for absent and present, but should not be used in annotations.

Characters involving well developed vs. small or absent entities

For example, a character involving the auditory foramen is coded with two states: 0, absent or small; 1, well developed. State 0 is recorded as polymorphic in Phenex:

E: auditory foramen, Q: decreased size E: auditory foramen, Q: absent

State 1 is recorded as:

E: auditory foramen, Q: increased size

Characters using monadic qualities

Monadic qualities are those that exist in a single entity, such as shape, and do not require another entity. For example, annotation of “sigmoid-shaped supraorbital bone” is entered as:

E: supraorbital, Q: sigmoid

Characters using relational qualities

Relational qualities are those that exist in an entity but require an additional entity in order to exist. For example, annotation of “parietal fused with supraoccipital” is entered as:

E: parietal, Q: fused with, RE: supraoccipital E: parietal, Q: separated from, RE: supraoccipital

Characters involving presence/absence of developmentally dependent entities

An example is bone develops_from cartilage.

Interhyal: (0) present and ossified; (1) present and cartilaginous; (2) absent

E: Interhyal bone, Q: present E: Interhyal cartilage, Q: present E: Interhyal cartilage, Q: absent(*)

(*)Note that because interhyal bone develops_from interhyal cartilage, we can simply state that interhyal cartilage is absent, and it is implied that interhyal bone is also absent.

Meristic data

Characters involving counts of entities are annotated using the “count” quality. Values for counts are entered in the “count” field. Note that ranges and lower or upper bounds can be recorded:

E: vertebra, Q: count, C: 33 E: vertebra, Q: count, C: 34-38 E: vertebra, Q: count, C: >38 E: vertebra, Q: count, C: =/>48

Refining terms by post-composition

Oftentimes the need arises to use a more granular term than is already present in the ontology, whether it is the anatomical entity or the quality. For example, to prevent ontology "bloat", regions, margins, and projections of a bone are not in the anatomy ontology, but the bone itself is, and the concepts of margin, relative location of the margin (anterior, posterior, ventral, dorsal, etc), or bony projection are too, or are in other ontologies (spatial aspect, for example). Similarly, the directionality of a phenotype (such as a rotation, or curvature) isn't necessarily present in PATO, but the component terms necessary to express it are. The act of combining terms on-the-fly into cross-product terms is called post-composition, as opposed to pre-composed terms that are already in the ontology.

Post-composed terms can be created in Phenex following the genus-differentia principle of defining terms, where one term serves as the genus, which is then differentiated using a relationship and a differentia term. Unlike pre-composed terms, post-composed terms do not have an ID, and hence are "anonymous." Therefore if the same post-composition is used multiple times, it has the same semantics, but not the same identity. For example, if one wants to assign multiple annotations to the same bony projection of the lateral ethmoid in the same specimen, using post-composed terms does not allow the identity of the anatomical structure between the annotations to be inferred.

The order in which the terms are composed is important if the composition relationship is not reflexive (a relationship is reflexive iff A rel B <=> B rel A). Most relationships are not reflexive. As a general rule, choose the more general part as the genus, and then use the relationship and differentia to narrow down. For example, for "bony projection of the lateral ethmoid" use "bony projection" as the genus, and use the relationship and differentia to narrow down which bony projection of the many that are possible you mean, such as using part_of for the relationship and "lateral ethmoid" as the differentia (formally, the "bony projection that is part_of the lateral ethmoid").

Note that semantically, the post-composed term is equivalent to a pre-composed term, provided the pre-composed term has both the inheritance relationship and the cross-product relationship properly recorded. For example, "bony projection of lateral ethmoid" is-a "bony projection", and "bony projection of lateral ethmoid" part-of "lateral ethmoid".

Refining entity terms on-the-fly

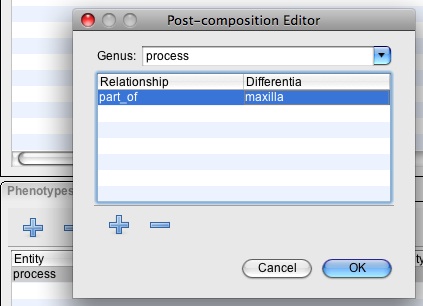

Open the post-composition editor box by right-clicking on an empty Entity cell within the "Phenotypes for State:" panel and clicking on “Edit Post-composed Term.”

To post-compose the entity “supraorbital projection”, type “bony projection” in the Genus field, click the “+” button to add a row in the table, type “part_of” in the relationship field, and type “supraorbital” in the differentia field. Click OK.

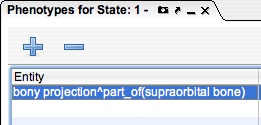

The post-composed term appears in the Entity field as:

Refining qualities using spatial terms

The Spatial Ontology is used to post-compose terms related to bone margins, surfaces, or regions. For example, the entity “anterior margin of frontal bone” is post-composed as follows:

Within the Post-composition Editor box, type “anterior margin” in the genus field and click the “+” button to add relationship = part_of and differentia = frontal bone. Click the OK button.

The post-composed term for anterior margin of frontal appears as: anterior margin^part_of(frontal bone)

As for semantics, identifiability, and rules for post-composing, the same applies as above for entity terms. Start with the more general term (for example, the "anterior margin") as the genus, then refine it using a relationship and a differentia term (for example, anterior margin that is part-of the "frontal bone").

Refining size qualities by making them relative

Because size qualities are monadic terms, comparison of size of one bone relative to another requires post-composition of the size quality. For example, the character “frontal length greater than parietal length” is entered as:

E: frontal Q: increased length, relative_to partietal

To post-compose the size quality, type ‘increased length’ in the quality field and click “comp” button. Select ‘relative_to’ in the relationship field and type ‘parietal’ in the differentia field., then click OK. Note that this post-composition follows the same rule of starting with the general terms ("increased length") as the genus, and then refining it with a relationship and a differentia (the increased length that is relative_to the "parietal").

Size qualities with ratio

For the characters in which a proportion or ratio is given in relating the length of one bone to another, the value of ratio is recorded. For example: Length of infraorbital 2: (0) over twice as long as infraorbital 1; (1) less than twice as long as infraorbital 1. This would be indicated in Phenex as follows:

E: infraorbital 2, Q: increased length, relative_to: infraorbital 1, Measurement: >2, Unit: ratio E1: Infraorbital 2, Q: decreased length, relative_to: infraorbital 1, Measurement: <2, Unit: ratio

The qualities are post-composed.

Serial homologues

Individual entities in a meristic series (e.g. vertebra 4 in a zebrafish vs. vertebra 4 in an eel), are not necessarily homologous across taxa. These can be handled in several ways, and we will discuss them here.

Evidence Codes

We record phenotype descriptions as properties of species, and annotations are assigned one of three evidence codes based on the level of evidence given by an author for phenotype observations. These specimen evidence codes are in an Evidence Codes Ontology that was developed by the broader biological community (see http://obofoundry.org/cgi-bin/detail.cgi?id=evidence_code). We have added evidence codes to this ontology, and we use the following in order below from strong to weak evidence.

Inferred from Voucher Specimen (IVS)

Used when an annotation is made on the basis of a phenotype description for a species or higher level group that is given by an author who explicitly references an observation of a voucher specimen(s). Voucher specimens are defined as those specimens with permanent museum catalog numbers. Thus it would be possible for a person to examine this particular specimen and observe the annotated phenotype.

- Note: if there is a matrix in the paper, the IVS evidence code is assigned to all annotations linked to the character list.

Traceable Author Statement (TAS)

The TAS evidence code covers author statements that are attributed to a cited source. Typically this type of information comes from review articles. Material from the introductions and discussion sections of non-review papers may also be suitable if another reference is cited as the source of experimental work or analysis. When annotating with this code the curator should use caution and be aware that authors often cite papers dealing with experiments that were performed in organisms different from the one being discussed in the paper at hand. Thus a problem with the TAS code is that it may turn out from following up the references in the paper that no experiments were performed on the gene in the organism actually being characterized in the primary paper. For this reason we recommend (when time and resources allow) that curators track down the cited paper and annotate directly from the experimental paper using the appropriate experimental evidence code. When this is not possible and it is necessary to annotate from reviews, the TAS code is the appropriate code to use for statements that are associated with a cited reference. Once an annotation has been made to a given term using an experimental evidence code, we recommend removing any annotations made to the same term using the TAS evidence code.

Nontraceable Author Statement (NAS)

The NAS evidence code should be used in all cases where the author makes a statement that a curator wants to capture but for which there are neither results presented nor a specific reference cited in the source used to make the annotation. The source of the information may be peer reviewed papers, textbooks, database records or vouchered specimens.