Taxonomic Rank Ontology

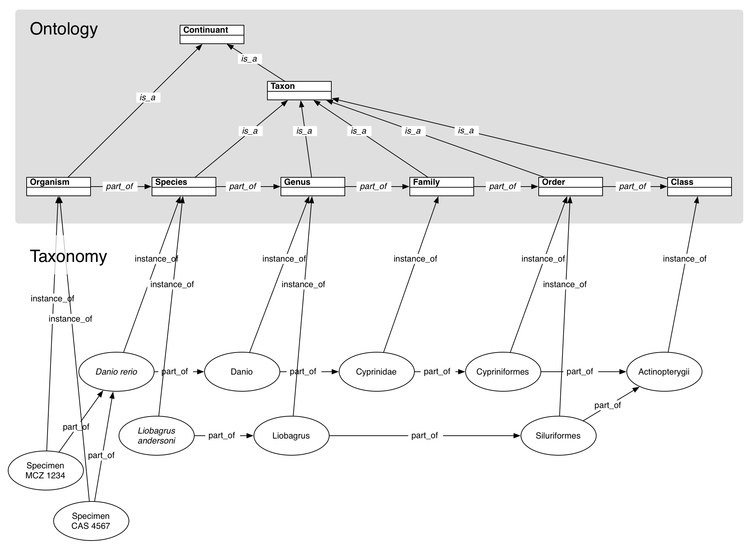

A taxonomic rank ontology allows particular taxa to be treated as historical individuals instead of as universal types.

Previous attempts to represent taxonomy using ontology usually include taxonomic groups as classes in the ontology. Individual organisms are seen as instances of those universal types. There could be an ontology term Mammal, such that Primates and Rodents are more particular types of Mammals (is_a descendants). Taxonomies are even often used as examples to help explain ontology inheritance to new users. This scheme fails to represent reality in several ways and is even misleading.

Problems with the "traditional" view

- The only criterion for inclusion within a taxonomic group is physical descent from a member of that group (we are assuming a taxonomy consistent with phylogeny). There are no universal properties one could ascribe to members of "Mammalia", besides things the members happen to share at this moment. "Hair" is often used an example of a Mammalian property; but of course its commonality is the result of its presence in the common ancestor of all mammals, and many mammals lack hair almost entirely. A mammal species that had no hair at all would nevertheless still be a mammal.

- Properties of a taxonomic group change through time: its geographic range, genetic and morphological diversity, etc. It can go extinct.

- Treating taxonomic groups as "classes" or "types" reinforces essentialist ideas of life forms, which evolutionary biology has completely overturned. Essentialist thought is a hindrance to understanding of the evolutionary process.

Instead treating taxa as types in an ontology, we can treat individual taxa as instances of the type Taxon, or more specifically as instances of some taxonomic rank.

Advantages

- Taxa are modeled as individuals.

- Taxonomic rank terms are ordered through their part_of relationships.