Matching Phenotypes

This page discusses the method developed and implemented in 2010-2011 for search for, and scoring, phenotype matches between taxa (Phenoscape) and zebrafish mutants (ZFIN).

Contents

Purpose

An important goal for the Phenoscape project is to be able to suggest candidate genes that may have contributed to evolutionary change. The way that we have proposed to do this is to search for changes in phenotype that appear as the result of mutations in model organisms and also appear as phenotype changes on an evolutionary tree.

Selecting Phenotypes from Taxon Annotations

The matching process involves matching changes in phenotype, not directly matching phenotypes. For phenotypes associated with mutants of model organism mutants, it is understood that they vary with respect to the wild type. For taxa, however, this means looking for taxonomic nodes where variation in a phenotype is observed among the children of the node. For example, there are nine species within the genus Aspidoras with annotations for the shape of the opercle bone. Of these, eight exhibit opercle bones with round shape, but the ninth (A. pauciradiatus) is annotated with a triangular opercle. In contrast, all three annotated species of the related Hoplosternum are annotated with a triangular opercle. Thus there is detectable variation in opercle shape within the children of Aspidoras, but not within Hoplosternum - suggesting that change in opercle shape has occurred somewhere among the descendants of Aspidoras. Once changes are identified, they are treated as variation in the affected entity at the level of the attribute parent of the qualities involved (e.g., shape).

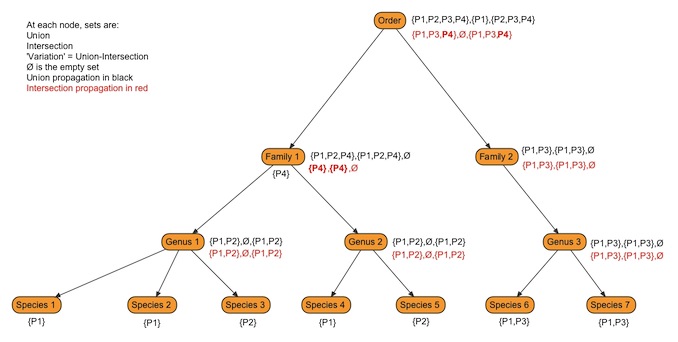

In more detail, variation is inferred by dividing up the set of phenotypes for each child taxa into subsets that share entities and have qualities that are subsumed by the same attribute (a quality that comes from the set of attribute qualities discussed in the Guide_to_Character_Annotation). Child taxa may have phenotypes in multiple groups, one group, or may have no phenotypes at all. Then, for each group represented in the phenotypes for any child taxon, both the union and the intersection of all the sets from child taxa that fall in the (Entity-Attribute) group are formed. If a child taxon has no phenotypes at all, it is ignored. If the child taxon has phenotypes in any groups, then the absence of a phenotype in the current group is just treated as an empty set in the union and intersection calculations. Variation within a group is determined by taking the set difference of the union and the intersection of the sets from child taxa. If the difference is empty, then the union and intersection are the same, which means all child taxa have the same phenotypes within the group, so no variation. Otherwise, the union and intersection differ and at least one child taxon has a different set of phenotypes. In this case, the parent taxon is indicated to have variation within in the Entity-Attribute group.

This approach to detecting variation within entity-attribute groups meshes well with the matching approach described in the next section. Note that ignoring taxa with no phenotypes reflects that nothing is known about such taxa and the presence of such taxa in the taxonomic tree should not affect the process of detecting change. The case where a taxon is annotated, but not in a particular group is taken, at present, to indicate variation that might not have been captured, either in the original publication matrix or the curation process. For example, the absence of a Basihyal bone is observed in Siluriformes, but there is no annotation regarding its presence or absence in sibling taxa, where it is, in fact present. Thus, the noted absence in one child and the lack of mention elsewhere is used to infer that variation is present in this character.

However, identifying variation also requires propagation of phenotype sets up the hierarchy. Continuing with the previous example, what variation could be assigned to the family-level parent of Aspidoras, Callichthyidae. Variation will depend on the phenotypes assigned to each genus in the family and how those are propagated to the family. We initially propagated the union sets within each entity-attribute group to higher taxa and added any phenotypes (few if any) annotated directly to the higher taxa. This seems reasonable as the union sets capture the full set of phenotypes found within the group. However, we found that this tended to inflate the amount of variation reported to the point that the base of the tree showed variation in nearly every entity-attribute group that subsumed phenotypes annotated in the KB.

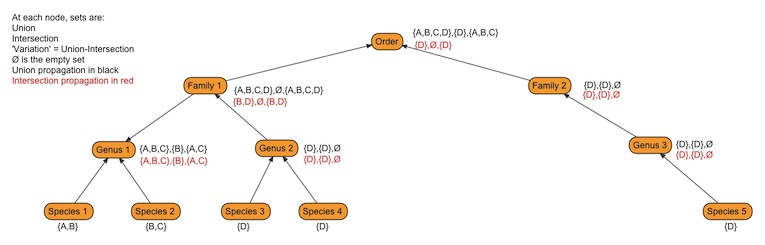

Changing to propagating intersection sets appears to reduce the inflation of propagated phenotype sets, and we are currently using it as our propagation method. There are some issues related to monotypic outgroups and propagating intersection sets (figure 2) that we are still investigating.

Figure 1 - This figure shows alternate methods of propagating phenotype sets.

Figure 2 - This figure illustrates the potential problem that propagating intersections has with monotypic outgroups.

Using attributes to limit the scope of quality comparisons

Because the focus of this analysis is comparing changes in phenotype, we compare phenotypes at a courser level that captures the set of states associated with a changing character. As discussed in the previous section, this is particularly important in capturing variation in taxa, but it also allows grouping gene annotated phenotypes that cause change in size of some entity (either increase or decrease) or color changes.

We use a set of asserted attributes (see above and the Guide_to_Character_Annotation) to group phenotype annotations into similar groups. Subsuming qualities all the way to this set attributes is not necessarily in all cases, for example, round and triangular are subsumed by 2-D shape. However, use of a consistent set of subsuming qualities simplifies the matching process.

This is currently implemented by mapping each phenotype to the corresponding phenotype consisting of the same entity and the closest subsuming attribute (e.g., opercle round will map to opercle shape). These mapped phenotypes are what the matcher actually compares.

Therefore, matching phenotypes is reduced to matching the entity component of changes that have a common attribute (so shape changes and color changes will never be matched).

ZFIN and Phenoscape use different (though partially overlapping) sets of qualities (from the PATO ontology) in constructing phenotype annotations.

Scoring matches of individual phenotypes

Each phenotype is linked to multiple entities via inheres_in_part_of relations. This relation holds between the entity in the phenotype as well as its is_a and part_of parents. The reasoner infers the closure of this relation, which means the KB contains inferred inheres_in_part_of relations between the entity and all the is_a and part_of parents of the entity in the phenotype.

Matching requires based on building a set of class expressions, subsumed by quality, that subsume the phenotype. This set of class expressions include all the phenotypes formed from an entity from the set of inheres_in_part_of parents and a quality that subsumes the quality specified in the phenotype. It also includes the quality terms that are subsumers (via is_a) of the quality in the phenotype. Because this set includes both quality terms from the PATO ontology and post-composed phenotype expressions, it is a set of class expressions.

The actual matching consists of taking the sets of subsuming class expressions from each of the phenotypes to be matched and forming the intersection, which is the set of common subsumers. Each of these subsuming expressions can be assigned an information content (IC). The match is scored as the IC of the common subsumer with the highest information content.

Note that under this scheme, an exact match may still score poorly if the selected common subsumer refers to an entity is high up in the anatomy hierarchy. For example round inheres_in bone matched against itself will have a lower score than straight inheres_in neural spine 1 against curved inheres_in neural spine 2 because the latter two share the subsumer straight inheres_in neural spine which will have a higher information content than round inheres_in bone.

Extending matches above the level of Entity-Attribute

Forming the full set of subsumers for a phenotype allows matches where the common subsumer is above the Entity-Attribute level. For example, eye size and eye color would match at eye physical object quality, since the later is a common subsumer. Because qualities above the attribute level will usually subsume large fractions of the total number of annotations, the information content of such subsumers will be relatively low. The full set of matches will be required for implementing Jaccard-type similarity metrics (e.g., the SimIC and SimJ metrics of Washington et al. (2009)). The higher level subsumers will also allow most phenotypes to match at levels below the top of the hierarchy (the class 'quality').

Scoring matches of sets of phenotypes (phenotypic profiles) associated with a gene or taxon node

Although the four measures of profile similarity used in the Washington et al. (2009) paper were plausible for comparing among phenotype profiles related to genes, we have doubts about their value for comparing profiles associated with taxonomic (phylogenetic) change against profiles associated with mutations in single genes. Addressing these doubts will require developing a framework, based on permuting phenotypes among profiles, to explore the behavior of phenotype match statistics. This will initially focus on maxIC (the greatest IC of any pair of phenotypes between the two profiles).

Profiles vary in size, and it is reasonable to assume that profiles with more phenotypes will, by chance, include phenotypes that yield higher scores for many statistics, in particular for the maxIC statistic. Therefore, to evaluate the significance of a phenotype match score, it should be compared against a null distribution of profile matches involving taxon and gene profiles with the same numbers of phenotypes. We will construct this null distribution by assigning phenotypes to profiles using sampling without replacement to build a set of profiles with the same size distribution as the actual dataset in the profile match report. We can't simply permute phenotypes (EQs) among profiles because of the possibility of assigning the same phenotype twice to a profile. Generated profiles will be paired (one taxon profile, one gene profile) and their test statistic score (e.g., maxIC) will be added to a distribution of scores in the appropriate cell in a table with rows corresponding to taxon profile sizes and columnts to gene profile sizes. Once the distributions have been filled, they will provide possible cut-off values for test statistic values of profile comparisons in the real data. For example

Similarity Metrics

Similarity Metrics (or more generally similarity measures) have been developed for scoring both pairs of phenotypes and for paired sets of phenotypes (i.e., phenotypic profiles). We are currently investigating a number of similarity metrics.

Max IC

ICCS

SimIC

SimJ

GCOS

=

Similarity Metrics (or more generally similarity measures) map from pairs of either singleton phenotypes or sets of phenotypes to real numbers.

Alternatives

Because of its dependence on the set of annotations, there is a real concern that IC may not be the most appropriate measure of similarity between terms an ontology with associated annotations.